toons

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Monday, August 21, 2006

Friday, August 18, 2006

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Why no blacks

I was asked to draw some illustrations for a book by Liz O'Rourke and Hazel Grant in 2005. The publishers wanted to know why my cartoons did not represent the diversity of our society. My response was published as a forward to Liz's book: Its all in the Record by Russel House Publishing.

Here is my unexpurgated reply jsut so you can all know why I draw this way:

Why are there no black people in my cartoons ? Why do these cartoons not represent the cultural and racial diversity of our society ?

Most of my colleagues find this charge incomprehensible. Here we are in South Africa, struggling to reconcile with each other and build a nation with forgiveness and justice at its heart. We have many deep and intractable problems which our racist past has left us. In our organization we work in over 25 townships developing small and micro-entreprises. Every day we deal with the poison that Apartheid fed our people. This poison is that we believe we are second-rate, throwaway people, conquered, enslaved and colonized people. As part of our programme, I run cartooning wokshops with children and adults, with corporate managers and artists and we engage the problems and opportunities that cartooning presents us.

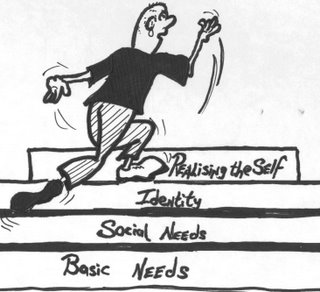

I don’t believe that cartooning is an art form but rather a broad approach to drawing that allows both drawer and reader the opportunity to recognize themselves in a fantasy world, a world of inordinate possibilities where the usual rules of daily life may be suspended and reworked to our advantage and often with humour. Cartoons allow us to see ourselves in the figures and situations drawn as impossibly simple and impossibly other. Cartoons give the child in all of us the chance to be and do anything that can be drawn.

With these thoughts I now turn to a number of arguments in defence of this charge:

Argument from perception

I only draw black lesbians. If you don’t see any black people, that’s your perception. The cartoonist relies in large measure on the reader’s common-sense stocks of knowledge to understand the cartoons. If the reader sees no black people then I have failed to access the reader’s sense of what black people look like in a cartoon.

Argument from common sense

Cartoons are a form of visual media most often combined with text and created to mediate a message, usually with humour. Unlike photography or caricature or potraiture, cartoons are not bound to a strictly representational rule for the subjects they draw but are more about situations than people. If cartoons were required to strictly represent populations, then the cartoons in this book and in almost every cartoon strip in the world would be banned.

Cartoons are objects of fancy, of the imagination of the cartoonist, they are often funny and are not meant to be taken as serious objects. They stand in a social category analagous to the court jester of old who was allowed much lattitude with respect to what they said and how they said it. Cartoonists are generally allowed a similar lattitude in their style, content and their abuse of the rules of art. If this were not so then cartoonists would be charged with age-ism, sexism, racism, and every other socially reprehensible crime. Animated cartoons are notorious for their displays of violence and all manner of criminal behaviour. Such behaviour is not acceptable in the real world and photographic depictions of real people doing these acts are rightfully deemed reprehensible. Our society however has no qualms with cartoonists drawing all sorts of vile and despicable acts of violence showing decapitations, murders and the like.

I doubt if any reader will complain about the cartoon in this book showing the person being run over by a bus or the poor tsunami survivor stranded on a giant book in the ocean, or the person being hit on the head by a coconut. All these situations, if they were represented on film would produce a wince at the very least and perhaps shock many readers. When they are drawn in a cartoon, these painful events do not even make the heart beat faster.

Yet I have not being challenged about the levels of violence depicted in my cartoons. This failure to challenge me about my potrayal of violence is not really a failure but exposes a commonsense understanding we all share, that cartoons are not “real”, they do not depict the real life experiences of real people but they are understood to present an idea, a circumstance, a feeling. Our common-sense stocks of knowledge have a category for “cartoons” and these cartoons are allowed great lattitude in what the characters drawn do and say. Those who would quibble may be regarded as lacking a sense of humour.

Argument from psychology

Visual media can be used for many purposes and these purposes in turn dictate the forms and subject matter. Icons for example, must contain the bones of a saint and other elements because the icon is itself an object of veneration, a holy thing. How the icon is used, dictates the form and content of the icon.

In like manner the cartoons I draw in this book are imbedded in the narrative text . The cartoons serve the author’s intention of gaining the attention of the reader and ensuring the reader retains the meaning contained in the narrative. Freud gave us three basic insights; The first is that all behaviour (including reading) is strictly motivated, nothing we do is simply capricious; the second insight is that some of our actions may derive from unconscious or subconscious motivations; and thirdly, our actions are motivated by emotional factors that are not strictly logical or intellectual.

Placing a cartoon next to a heading in this book offers the reader the opportunity to integrate the meaning of a section of the book using parts of themselves that are not strictly intellectual but that may resonate at an emotional, subconsious level within the reader. Humour helps the reader to absorb the content, even perhaps by-passing the more consciously constructed and maintained perceptual filters we use when reading words.

Argument from technique

There are at least six gambits that cartoonists use to draw black people. Each strategy is in some way flawed and unsatisfactory.

1. Using colour may be the best way out but there is a limited budget (unless the editors are happy to pay me an extra 500 smackers to colour the ‘toons) and colour printing is still very expensive. In addition, the cartoons are designed to assist and support the text, not upstage the text. A colour cartoon may well overwhelm the heading and thus the whole point of drawing the cartoon to reinforce the meaning of the text will be lost.

2. Using racialized features such as crissy hair, thick lips and a squashed flat nose would simply be reinforcing untrue and silly racial stereotypes

3. Using shading in black line drawings on white paper generally denotes texture and grittiness to the surface. It perhaps still needs to be said that black people do not have rougher, grittier skins than whites.

4. Using anthropomorphic figures is not funny to me and I hate drawing animals.

5. Using accessories can be just as stereotyping as drawing crude racial features. Not all people who have dreadlocks are pot smoking rastas. Not all lesbians wear overalls with peace signs on them. Not all indians wear turbans or fezzes.

6. Using a disclaimer to the effect that “all the figures drawn in this cartoon do not represent any real person and is just the product the cartoonists fevered imagination” would take up space and detract from the purpose the cartoon, which is to support the narrative.

There seems little point in representing the racial and cultural diversity of a society when the techniques used to do so reinforce harmful stereotypes of the people so diversely represented. So we live in a diverse society where black people and women and other groups are represented in cartoons as stupid or silly. Is this the kind of diversity you really want represented ? There is an irony here in so far as those who tender this argument use racial and cultural diversity both as a topic and a resource for what they argue.

What is needed is something more profound, more ethically sound, more transformational than the usual cartooning techniques deployed presently. To this end I have crafted a set of stylistic pointers to drawing cartoons which may lead cartoonists and readers away from the mere replication of racial sterotypes.

Argument from style

I have deliberately chosen a style that

1. Is minimalist to the extent that there are not many details drawn.

2. The line drawings are androgynous, most of the figures could be male of female. I have stripped them of cues that engender or racialize them.

3. I have chosen to render figures and situations that reinforce the heading as much as possible and do not distract the reader from the text.

4. I only shade clothing to add more presence to the picture.

5. I have attempted to draw cartoons that are as transparent as possible so that the author’s meaning can be impressed upon the reader without any other issues intervening or perceptual filters coming into play.

This stylistic strategy allows me to support the narrative and meaning of the book without relying on the cartoonists’ usual shorthand in depicting gender or race. My skill is limited and I may fail to achieve these aims but it is nonetheless a deliberate and carefully chosen strategy on my part.

Argument from politics

I’m an anarchist. I find representational politics and the notion that someone or something can represent me demeaning and sterile. I prefer a more iconic sort of politics. I support the idea that we can only reperent ourselves, that leaders are precisely that, leaders. Not “representatives” of us or our interests. In like manner, my cartooning cannot claim to represent any real person or situation. The reader uses the images and words they read to construct in their mind’s eye the meaning that they understand.

It is clear that there is a movement within our society and especially among social studies graduates which argues that presenting images that reflect the racial and cultural diversity of our society in the media will lead readers to more readily accept difference in social settings. This may or may not be true. Is it true that seeing hours of violent cartoons on the television leads children and adults to be more violent in their social relationships ? Some argue vehemently for, and some against this agrument. If the media does have such power, is it really our business to be involved in social engineering ? However, if the Media lacks such power, then why insist on “representivity” ?

Publishers and those involved in the media need to become the change they want. Much of the publishing industry is inherently racist and exploitative. It can be reliably estimated that 71% of the paper that makes up this book probably came from a plantation or old forest wood in some ex-colony of our disunited Queendom er… Commonwealth. Commonwealth being a seriously ironic word given that many of the members of the commonwealth are so poor they cannot afford to repay the interest on the loans made to them by wealthy colonizing countries who fund the World bank and IMF. The paper and ink industries are dominated by multinational corporations such as SAPPI and others who manage plantations of millions of non-inigenous trees or loggers who destroy the indigenous plant and animal life of other regions. These same multinationals employ local people, mostly black, on extemely low wages or as indentured labour and use pulping methods that pollute vast areas.

Despite this huge multinational process, there are those in the welfare field who seek to adhere to codes of publishing and employment that attempt to ensure “the cultural diversity “ of our society is represented in the graphic images published and the people employed in all organizations. This political movement is known by many names such as “Affimative Action” and so on. It has been practiced in many countries. In Hackney and other local authorities in the 1980’s, social work posts were kept vacant for years because not enough of the people appllying for the posts represented the demographics of the area. In the USA, sitcoms produced for various television networks must include black actors in powerful roles. In South Africa, large corporate companies and state departments reserve posts for black people. This unfortunate movement is a strerile and fomulaic approach to transformation in any society. Sterile, because no sets of rules or policies or charters or laws can transform human relations. It is a policy wrought out of desperation that reasons if we can’t change the way people think then we are going to change the way people do things, by force. All that this movement achieves is the reinforcing of the system which ensures the exclusion of certain groups of people.

Colleagues of mine who have “benefited” from Affirmative Action in South Africa, complain that they are often given token positions and are simply employed because of the colour of their skin and not for their skills. Martin Luther’s dream was that we could live in a world where people would be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the contents of their character. Affirmative Action Cartooning cannot help us create a society at ease with cultural and racial diversity when the industry that publishes cartoons remains a powerful homogenizing agent.

An iconic politics requires that social action transforms systems and organizations by building transformed organizations and systems. I am part of a fellowship, not unlike Tolkien’s “Fellowship of the Ring”, that seeks to change this world and to build solutions to its problems using organizations and people who see themselves as global citizens. The Ashoka Fellowship is made up of about 1500 fellows wordwide. Less than those who have climbed Mount Everest.

We need you to become the change you want in this world.

Let me introduce you to some of our number;

· Nicole Rycroft from Canada runs Markets Initiative and had by 2003 convince 32 Canadian publishing houses to use Ancient forest-friendly book grade paper.

· Jose Campana from Uruguy runs Book Banks where children are taught to restore books and maintain school libraries.

· Magda Iskander from Cairo has establsihed homebound elder care as a profession in Egypt.

· Duke Kaufman runs the Sanctuary using old mine hostels in South Africa. The Sanctuary is the largest Aids orphanage in the world.

· Socorro Guteres in Brazil runs the Centre for Black Culture of Maranhao.

· Krzysztof Cyzewski in Sejny, Poland runs the Borderland Foundation and wants to document and publish the achievements of young people in the ethnically diverse region of Sejny.

· Kim Feinberg in South Africa runs the Foundation for Tolerenace Education.

· Rajidt Malley from Indonesia runs YLL and works with Gerperindo to highlight the illegal logging of indigenous forests.

Go on the internet and “Google” them.

We Ashoka Fellows need your support, we need you to work with us, not to potray the ethnically and culturally diverse society we live in, but to actually and in practical ways, empower and give dignity to racially and ethnically diverse people who are exploited by British companies (including book printers and social services organizations) and by those with wealth and power. To join with us, to support our Fellowship is not representational politics. This is the politics of the icon. This is becoming the change you want.

I hope that these arguments act as a sufficient defence against the charge that my cartoons do not represent the racial and cultural diversity of our society.